Understanding Self-Compassion

A Guide to Treating Yourself with Kindness

Introduction

What if the harshest critic you face every day is the voice inside your own head? For many adults, this internal dialogue is relentlessly negative. We speak to ourselves in ways we would never dream of speaking to someone we care about. When we make a mistake at work, forget an important deadline, or struggle with a personal challenge, we respond with a barrage of criticism that would be considered cruel if directed at anyone else. Yet somehow, we have come to believe that this self-punishment is necessary, even virtuous.

For much of the twentieth century, Western psychology focused on self-esteem as the cornerstone of psychological wellbeing. We were taught that feeling good about ourselves required being special, above average, or better than others. While self-esteem has its place, it has proven to be a volatile companion. It tends to abandon us precisely when we need it most, in moments of failure, embarrassment, or inadequacy. When life falls apart, the pursuit of high self-esteem can collapse into harsh self-criticism, leaving us vulnerable to anxiety, depression, and profound isolation.

Enter self-compassion. Unlike self-esteem, which is based on evaluation and comparison, self-compassion is rooted in acceptance and care. It does not ask you to be better than others or to hide your flaws. Instead, it asks you to treat yourself with the same kindness, warmth, and understanding that you would naturally offer to a dear friend in a moment of crisis. It is a concept that is both ancient, drawing from Buddhist contemplative traditions, and cutting-edge, supported by over two decades of rigorous empirical research.

This article serves as a comprehensive guide to understanding, developing, and integrating self-compassion into your life. We will explore the pioneering work of researchers like Dr Kristin Neff and Professor Paul Gilbert, examine the neuroscience of why being kind to yourself actually changes your physiology, dispel persistent myths, and provide detailed, evidence-based techniques you can begin practising today. Whether you are struggling with anxiety, recovering from depression, navigating trauma, or simply seeking a healthier relationship with yourself, self-compassion offers a scientifically validated path forward.

Part One: What Self-Compassion Really Means

To truly practise self-compassion, one must first understand what it is and, perhaps more importantly, what it is not. Self-compassion is not self-pity, self-indulgence, or making excuses. It is not about lowering your standards or avoiding accountability. Rather, it is a dynamic, multidimensional skill that fundamentally changes how you relate to your own suffering.

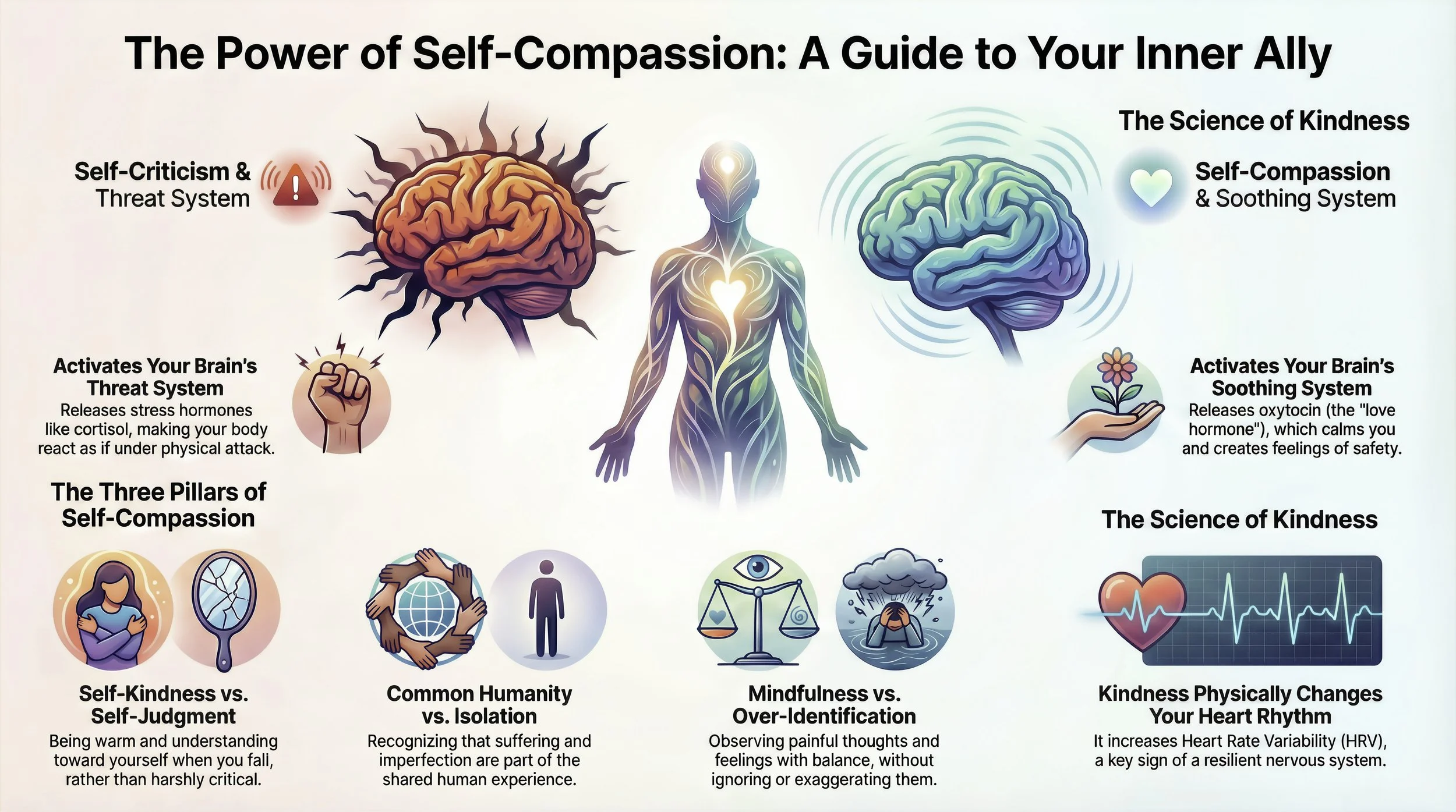

Kristin Neff’s Three-Component Model

Dr Kristin Neff, an educational psychologist at the University of Texas at Austin, pioneered the scientific study of self-compassion in the early 2000s. Drawing from Buddhist psychology, she observed that while Western culture readily embraces the concept of compassion for others, it remains deeply ambivalent about extending that same compassion inward. Her foundational research offered the first formal definition and measurement of self-compassion, identifying three core components that work together as an integrated system.

Self-Kindness

The first component involves being warm and understanding toward ourselves when we suffer, fail, or feel inadequate, rather than attacking ourselves with harsh criticism. Consider for a moment how you speak to yourself when you make a mistake. If you drop something, forget an appointment, or say the wrong thing in a meeting, what is the immediate internal monologue? For many people, it is a barrage of insults: “You idiot,” “You can’t do anything right,” “What is wrong with you?” This is the voice of self-judgement. It is cold, cutting, and intolerant of imperfection.

Self-kindness is the active reversal of this habit. It does not mean denying that a mistake was made. Instead, it changes the emotional tone of the response. It acknowledges the difficulty of the situation and offers support. It is the difference between a coach who screams at a player for missing a goal and a coach who says, “That was a tough shot. Take a breath, and let’s focus on the next play.” Self-kindness recognises that being imperfect and experiencing life difficulties is inevitable, so we might as well be gentle with ourselves when we confront these painful experiences.

Common Humanity

The second component distinguishes self-compassion from self-pity. When we are in the grip of self-judgement or suffering, we tend to fall into an irrational state of isolation. We feel as though we are the only person in the world who is struggling. We look at social media or the outward lives of our peers and see only success and happiness, concluding that something must be uniquely wrong with us. This is what Neff calls the “egocentric trap” of suffering. It separates us from others, making us feel broken and alone.

Common humanity is the wisdom that recognises suffering and personal inadequacy as part of the shared human experience. It is something that we all go through rather than something that happens to “me” alone. When we fail an exam, lose our temper with our children, or feel overwhelmed by anxiety, we are not alone. Millions of people are experiencing similar struggles at this very moment. This recognition connects rather than isolates. It moves the experience of pain from a personal failure to a shared reality. Shame thrives in secrecy and isolation. By illuminating the universality of our struggle, common humanity dissolves the shadows where shame lives.

Mindfulness

The third component is mindfulness, the foundation upon which the other two rest. You cannot be kind to yourself or recognise your common humanity if you are not even aware that you are in pain. Mindfulness involves holding painful thoughts and feelings in balanced awareness rather than suppressing them or becoming completely swept away by them. It means neither ignoring your pain nor exaggerating it, but simply acknowledging that this moment is difficult.

The specific role of mindfulness in self-compassion is to prevent what Neff calls “over-identification.” Over-identification occurs when we get swept away by our negative reactivity. We become the emotion. We are not just feeling sad, we are sadness. We ruminate obsessively on what went wrong, narrowing our focus until the problem is the only thing that exists in our universe. Mindfulness offers a balanced approach that allows us to step back and say, “This is a moment of suffering” or “I am feeling a wave of anxiety right now.” This slight distance creates the space necessary to choose a compassionate response rather than reacting out of habit.

These three elements interact dynamically. Mindfulness prevents harsh self-judgement by creating psychological distance. Self-kindness reduces the emotional impact of difficult experiences, making it easier to maintain balanced awareness. And recognising that others share your struggles naturally reduces the tendency to blame yourself harshly for your perceived failings. Since Neff’s original papers, over 7,000 research studies have validated the concept, making self-compassion one of the most robust findings in contemporary psychology.

Part Two: Why Self-Compassion Differs From Self-Esteem

Perhaps the most clinically significant distinction in this field is between self-compassion and self-esteem. Though both are positively related to psychological wellbeing, they work in fundamentally different ways that have profound implications for mental health.

Self-esteem requires evaluating yourself positively, standing out in a crowd, and feeling special or above average. It is inherently comparative and contingent on outcomes. When you succeed, self-esteem soars. When you fail or feel inadequate, it crashes. Research by Neff and Roos Vonk involving over 2,000 participants found that self-esteem fluctuates dramatically based on performance, appearance, and social approval, creating an emotional roller coaster where your sense of worth rises and falls with your latest success or failure.

Self-compassion, by contrast, does not require you to feel better than anyone else or to evaluate yourself positively at all. It simply asks that you treat yourself with the same care you would offer someone you love. Crucially, self-compassion remains available precisely when you need it most, in moments of failure, embarrassment, or inadequacy, when self-esteem typically deserts you. You do not have to perceive yourself as better than others. You simply acknowledge you are a flawed human among others, worthy of care despite imperfections.

Research consistently shows that self-compassion provides more stable feelings of self-worth over time, is less dependent on external circumstances, and is completely unrelated to narcissism, while self-esteem has robust associations with narcissistic tendencies. A longitudinal study with adolescents found that students with low self-esteem but high self-compassion were psychologically healthier a year later than those low in both, suggesting that self-compassion can buffer the negative effects of struggling with self-esteem.

This distinction matters enormously in clinical practice. Therapies that aim to boost self-esteem may inadvertently teach people that their worth depends on being exceptional, which is by definition something most people cannot achieve. Self-compassion offers an alternative foundation for psychological wellbeing that does not require winning at life to feel okay about yourself.

Part Three: The Neuroscience of Self-Compassion

One of the most compelling arguments for self-compassion comes not from philosophy but from hard physiology. Sceptics often view self-compassion as “soft” or “fluffy,” but the biological data suggests it is a robust physiological intervention that fundamentally alters how our bodies function under stress.

Paul Gilbert’s Three Emotion Regulation Systems

While Neff provides the “what” of self-compassion, British clinical psychologist Professor Paul Gilbert provides the “why” through the lens of evolutionary psychology. His Compassion Focused Therapy is essential for understanding why we are so prone to self-criticism and why self-compassion is a biological necessity rather than just a psychological luxury.

Gilbert proposes that the human brain has evolved three distinct emotional regulation systems, often visualised as three circles: the Threat System, the Drive System, and the Soothing System. Understanding these systems helps us realise that our struggle with self-criticism is not a personal failure but a biological pattern in how our ancient brains navigate the modern world.

The Threat System is the oldest part of our emotional programming, associated with brain structures like the amygdala. Its primary function is protection and survival. It is constantly scanning the environment for danger. When triggered, it floods the body with adrenaline and cortisol, preparing us for fight, flight, or freeze. In the ancestral environment, threats were physical predators or rival tribes. In the modern world, threats are rarely physical. Instead, they are social and internal: the fear of rejection, the fear of failure, the fear of not being good enough. The inner critic is essentially the Threat System turned inward. When we criticise ourselves, we are attacking ourselves, and our body responds as if we are under actual physical attack. Neuroimaging research has shown that self-criticism significantly activates the anterior insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and amygdala, the same brain regions that light up when you face an external threat.

The Drive System is responsible for motivating us to seek out resources, achieve goals, and compete. It is fuelled by dopamine and produces activated positive feelings such as excitement, motivation, and vitality. In our achievement-oriented society, we spend a vast amount of time in this system, constantly chasing the next promotion, the next purchase, or the next milestone. While the Drive System is necessary for progress and survival, it can easily become overactive. When we fail to achieve our goals, we can crash from Drive directly into Threat, feeling like failures. Many adults oscillate exclusively between Threat and Drive, leaving them exhausted and burnt out.

The Soothing System is the system that many adults have neglected or simply never learned to cultivate. It is responsible for “rest and digest” functions and is linked to feelings of contentment, safety, and connection. It is chemically mediated by oxytocin and natural opiates. The function of this system is to help us settle, soothe distress, and promote bonding. It signals to the brain that “you are safe, you are enough, there is nothing you need to do right now.” Self-compassion is essentially the practice of manually activating the Soothing System. When we are kind to ourselves, we are tapping into this mammalian caregiving circuitry.

Gilbert’s model explains why self-criticism is so damaging: it keeps us stuck in the Threat System. It also explains why self-compassion is the cure: it stimulates the Soothing System, downregulating the threat response and restoring physiological and emotional balance.

Heart Rate Variability and the Vagus Nerve

The mechanism connecting self-compassion to physical health is the autonomic nervous system, specifically the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve is the longest cranial nerve in the body, running from the brainstem down to the heart, lungs, and digestive organs. It is the primary data highway for the parasympathetic nervous system, the branch responsible for calming the body down after a stress response.

Research indicates that self-compassion practices effectively stimulate the vagus nerve. When we speak kindly to ourselves or engage in soothing touch, we increase “vagal tone.” A key marker of vagal tone is Heart Rate Variability (HRV). High HRV is a sign of a healthy, resilient nervous system that can adapt flexibly to stress. It means the heart can quickly speed up when needed and slow down just as quickly when the threat has passed. Low HRV is associated with anxiety, depression, and cardiovascular disease.

Studies have shown that individuals with higher levels of self-compassion exhibit higher HRV and lower skin conductance when faced with stress. Conversely, self-criticism activates the sympathetic nervous system, increasing heart rate and cortisol levels. A study by Petrocchi and colleagues found that compassionate self-talk increased HRV and soothing positive affect, effects that were even amplified when participants looked at themselves in a mirror while speaking. This suggests that we can literally talk our bodies out of a stress state and into a state of safety.

When you practise self-compassion, you are not just changing your mind. You are changing your heart rhythm. You are sending a bio-signal of safety to your amygdala.

Oxytocin and the Chemistry of Care

The chemical war within us is often between cortisol, the stress hormone released by the Threat System, and oxytocin, the love and bonding hormone released by the Soothing System. Self-criticism is a form of self-harassment that keeps cortisol levels chronically high, leading to inflammation, suppressed immunity, and anxiety.

Self-compassion, on the other hand, mimics the effects of being cared for by a loved one. When we offer ourselves warmth and understanding, we trigger the release of oxytocin. Oxytocin does more than just make us feel “warm and fuzzy.” It directly reduces cortisol, lowers blood pressure, and facilitates social connection. It is the “anti-stress” hormone. One study showed that simply imagining receiving compassion led to lower cortisol levels and a more relaxed physiological state, as participants’ hearts “opened up” rather than staying defensive. By actively generating feelings of warmth and care, we are providing our bodies with the biochemical resources needed to heal and repair.

Part Four: The Research Evidence

The evidence for self-compassion is substantial and growing. A foundational meta-analysis by MacBeth and Gumley, examining 14 studies using the Self-Compassion Scale, found a large effect size for the relationship between self-compassion and reduced psychopathology. This means higher self-compassion is strongly associated with lower levels of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress. A subsequent meta-analysis by Zessin and colleagues, analysing 79 samples with over 16,000 participants, found a medium-to-large effect for the relationship between self-compassion and wellbeing, with particularly strong effects for cognitive and psychological wellbeing.

The evidence from intervention studies is equally compelling. A 2019 meta-analysis by Ferrari and colleagues examined 27 randomised controlled trials and found significant improvements across multiple outcomes. The largest effects were seen for eating behaviours and rumination, with self-compassion interventions producing changes that would be considered “large” by research standards. Depression, anxiety, stress, and self-criticism all showed “moderate” improvements. Importantly, gains in depression were maintained at follow-up assessments, suggesting lasting rather than temporary benefits.

People who are more self-compassionate tend to experience better mental health overall. They are much less likely to be depressed, anxious, or stressed, and much more likely to be happy, resilient, and optimistic about their future. Self-compassion is strongly linked to greater life satisfaction, emotional resilience, and even wisdom and curiosity, while also being associated with less rumination, perfectionism, and self-criticism.

Part Five: Dispelling the Myths

Before one can fully embrace self-compassion, the barriers of misconception must be dismantled. In Western culture, we are often taught that we need to be hard on ourselves to succeed. These myths act as psychological blockades, preventing us from accessing the very tools that could help us most.

“Self-Compassion Makes You Lazy”

The most pervasive fear is that if we stop criticising ourselves, we will become complacent and unmotivated. Many people believe the inner critic is the only thing driving them forward. “If I don’t beat myself up, I’ll never get anything done.”

Research completely refutes this. In fact, the opposite is true. Fear-based self-criticism undermines motivation. It creates performance anxiety and a fear of failure so intense that it can lead to procrastination and giving up. When we are driven by the threat of self-punishment, we become risk-averse. We are afraid to try because the cost of failure, the self-abuse that will follow, is too high.

Self-compassion, conversely, fosters a “growth mindset.” Because self-compassionate people know they will not attack themselves if they fail, they are less afraid of failure. They are more willing to take risks, try new things, and pick themselves up after a setback. A meta-analysis examining 26 studies with over 7,600 participants found a reliable positive correlation between self-compassion and motivation. In one experiment, students who were encouraged to be self-compassionate after failing a test spent more time studying for the next test than those given a self-esteem boost or no intervention. Self-compassionate people are also more likely to take personal responsibility for their mistakes and try to repair them, because their ego is not devastated by the admission of error. They are motivated by care rather than fear. They want to achieve because they care about themselves and their potential, not because they are terrified of being worthless.

“Self-Compassion Is Self-Pity”

Many people conflate self-compassion with “wallowing” or feeling sorry for oneself. This is a fundamental misunderstanding of the Common Humanity component. Self-pity is an immersive, isolating state. When we are in self-pity, we feel like the only victim in the world. We exaggerate our suffering and ignore the suffering of others. It is a “me-focused” state of separation.

Self-compassion is the antidote to self-pity. By reminding us of common humanity, that everyone struggles and this is part of life, it breaks the isolation of self-pity. It broadens our perspective rather than narrowing it. It allows us to see our situation clearly through mindfulness without exaggeration. Research confirms that people with higher self-compassion are actually less likely to engage in self-pitying ruminations. They acknowledge the pain without becoming the pain.

“Self-Compassion Is Weakness”

There is a cultural stigma that kindness is “soft” and criticism is “tough.” Therefore, self-compassion is often seen as weak.

In reality, self-compassion is a source of immense resilience. It is the emotional muscle that allows us to cope with tragedy, divorce, trauma, and failure without falling apart. Studies on trauma recovery show that self-compassion is a key predictor of who develops PTSD and who does not. Those who can self-soothe are better able to process traumatic events. It requires courage to turn toward our pain with kindness rather than running away from it or numbing it out. Self-compassion provides the emotional safety needed to acknowledge difficult truths, making it a stance of strength, not weakness.

Part Six: When Self-Compassion Feels Difficult

If self-compassion is so beneficial, why is it so hard for some people? Gilbert’s research identified “fears, blocks, and resistances” that prevent people from accessing compassion for themselves. He developed the Fear of Compassion Scales, which measure fear of expressing compassion to others, fear of receiving compassion from others, and, most clinically relevant, fear of self-compassion itself.

Fear of Self-Compassion

Research consistently shows that fear of self-compassion is linked to self-criticism, insecure attachment styles, depression, anxiety, and importantly, shame memories and experiences of childhood abuse or neglect. People who grew up in critical, controlling, or abusive environments learned to treat themselves as they were treated. For these individuals, their inner critic feels familiar and protective, even as it causes suffering. Self-compassion, by contrast, feels foreign and threatening.

Common fears include believing that self-compassion will make you weak, that you don’t deserve it, that you will lose your edge, or that letting down your guard will open you to more pain. An interesting gender finding from Gilbert’s research is that men scored significantly higher on fear of self-compassion than women, possibly reflecting cultural expectations around masculinity and emotional vulnerability.

The Backdraft Phenomenon

The “backdraft” phenomenon, a term borrowed from firefighting by Christopher Germer and Kristin Neff, describes the discomfort that can arise when people first begin practising self-compassion. Just as a fire can intensify when fresh oxygen enters, old emotional wounds can flare when met with kindness for the first time. Backdraft can manifest as waves of grief or sadness, intrusive negative thoughts, physical discomfort, or the urge to withdraw from the practice entirely.

Germer and Neff emphasise that backdraft is not a sign that self-compassion is causing harm. Rather, it indicates that old pain, previously kept at bay through self-criticism or emotional avoidance, is now being acknowledged. As they explain, the discomfort of backdraft is not created by self-compassion practice but by what was already there. The pain that was frozen is now flowing.

The solution is not to abandon self-compassion but to proceed gently. This means going slowly and not forcing yourself to feel compassion if it feels overwhelming. It means using grounding techniques, such as focusing on the soles of your feet or an external object, to stabilise the nervous system. It means retreating to ordinary self-care activities like having a cup of tea or going for a walk until the intensity subsides. And it means simply labelling the experience, as saying “This is backdraft” can reduce the fear of the emotion. For people with histories of severe trauma, working with a trauma-informed therapist trained in Compassion Focused Therapy is recommended to navigate these experiences safely.

Part Seven: Self-Compassion and Mental Health

Self-compassion is not just a self-help tool. It is a clinical intervention with proven efficacy for a range of mental health conditions.

Anxiety

Anxiety is often the Threat System stuck in “on” mode, constantly scanning for danger. Self-compassion works for anxiety because it activates the Soothing System, which acts as a physiological brake on the anxiety response. It downregulates the sympathetic nervous system. Research in people with generalised anxiety disorder found that higher self-compassion was associated with lower heart rate during stress and increased heart rate variability, suggesting both psychological and physiological stress buffering. For social anxiety specifically, self-compassion appears to work by improving emotional regulation and reducing the isolation and self-judgement that amplify social fears.

Depression

Depression can be the result of a “shutdown” response after prolonged stress, often accompanied by intense self-attacking thoughts and rumination. The relationship between self-compassion and depression is particularly well-documented. Higher self-compassion predicts lower depressive symptoms up to five months later in prospective studies. For people with treatment-resistant depression, those who have not responded to conventional therapies, Compassion Focused Therapy produced remarkably large improvements in one study.

Self-compassion breaks the cycle of rumination. Depressed individuals often get stuck in a loop of “I’m worthless, I’m a failure.” Mindfulness allows them to catch these thoughts, and self-kindness allows them to replace the internal whip with a supportive hand. The mechanism appears to involve reducing the harsh self-judgement and rumination that fuel depressive episodes while increasing self-acceptance and emotional regulation.

Trauma and PTSD

For survivors of trauma, the world and often their own body feels unsafe. Trauma survivors often carry immense shame and self-blame. This shame keeps the Threat System highly active. Self-compassion is crucial for trauma recovery because it directly addresses shame. It helps survivors reframe their responses to trauma not as signs of weakness but as survival strategies that deserve respect. It provides a sense of internal safety that is often missing.

A 2021 meta-analysis by Luo and colleagues found a medium protective effect of self-compassion against PTSD symptoms. Self-compassion helps trauma survivors by reframing suffering as part of shared human experience rather than evidence of personal defectiveness, reducing avoidance of painful emotions, and facilitating post-traumatic growth. Notably, self-compassion does not just reduce symptoms but appears to help people find meaning and personal development through their struggles.

Part Eight: Developing Self-Compassion in Practice

Understanding the theory is the map. Practice is the terrain. Self-compassion is a skill, much like playing an instrument or learning a language. It requires repetition to rewire the brain’s neural pathways. The Mindful Self-Compassion programme, developed by Christopher Germer and Kristin Neff, distils years of research into teachable skills. Since the first programme was offered in 2010, over 250,000 people have participated worldwide. The following techniques are considered the gold standard in developing this capacity.

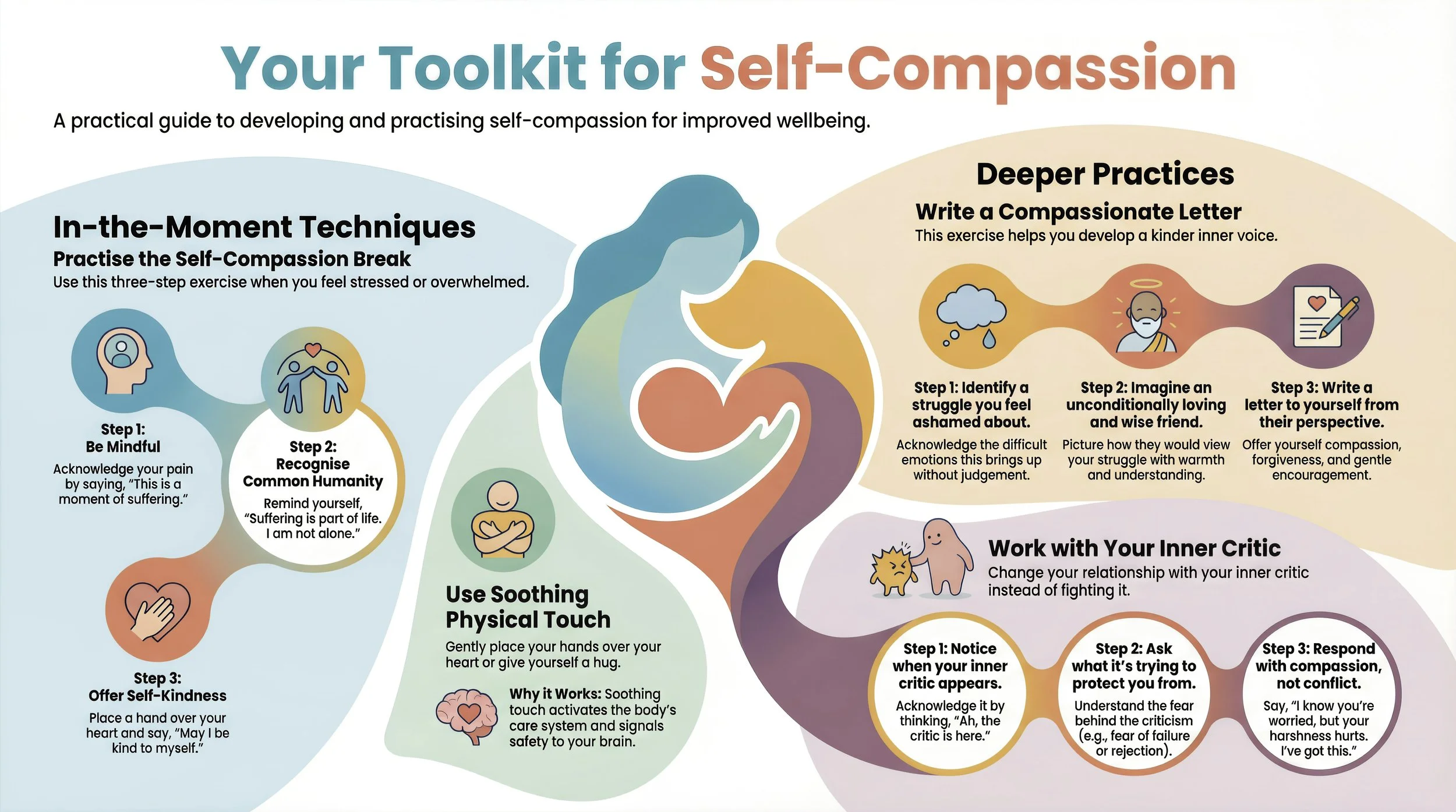

The Self-Compassion Break

This is the quintessential “emergency response” practice. It is designed to be used in the heat of the moment when you are feeling stressed, overwhelmed, or self-critical. It takes only a few minutes and explicitly activates all three components of self-compassion.

When you notice you are suffering or struggling, pause and move through three steps. First, acknowledge that this is a moment of suffering. You might say to yourself “This is really hard right now” or simply “Ouch, this hurts.” This is the mindfulness step. It validates your experience and turns you from a victim of the experience into an observer.

Second, remind yourself that suffering is part of being human. You might say “Other people feel this way too” or “I am not alone in this.” This is the common humanity step. It breaks the isolation and reminds you that you are not broken, you are human.

Third, place your hands over your heart or another comforting location and offer yourself words of kindness. You might say “May I be kind to myself” or “May I give myself what I need right now.” This is the self-kindness step. If these phrases feel too abstract, use specific phrases that meet your need, such as “May I accept myself as I am” or “May I be patient with myself” or “May I forgive myself.”

The power of this practice lies in its simplicity and portability. It can be used any time, day or night, when you notice you are suffering and need a dose of kindness. It only takes a moment, but it directly counters the habitual stress response with a care response.

Soothing Touch

Because the Threat System is biological, we often need a physical intervention to switch it off. We are mammals, and mammals respond to warmth and touch. Research shows that warm physical touch activates the body’s caregiving system, triggering the parasympathetic nervous system and releasing oxytocin. Your body does not distinguish much between comfort from someone else and comfort from yourself. Either way, slow breaths and a warm touch can lower distress.

Experiment with placing both hands over your heart and feeling the warmth of your palms against your chest. Notice the rhythmic rise and fall of your breathing beneath your hands. Other options include cradling your face gently in your hands, giving yourself a gentle hug by crossing your arms and holding your shoulders, or placing one hand on your heart and one on your belly. The key is finding a gesture that feels genuinely soothing rather than mechanical.

This technique bypasses the cognitive brain and speaks directly to the vagus nerve, signalling safety. It may feel awkward at first, but your nervous system does not judge. It simply responds to the stimulus. Once you find what works for you, this touch can be used discreetly in public situations whenever you need a moment of comfort.

Compassionate Letter Writing

This exercise utilises your cognitive capacities to retrain your internal narrative. It helps to externalise the compassionate voice until you can internalise it.

Begin by identifying something about yourself that you struggle with or feel ashamed about. Take a moment to acknowledge how this makes you feel, and allow yourself to feel these emotions mindfully without suppression or exaggeration. Then, imagine an unconditionally loving friend who sees all of you, your strengths and your struggles, your history and your hopes. This friend understands the causes and conditions that shaped you. In their wise eyes, your flaws do not make you any less worthy of love.

Now, write a letter to yourself from this compassionate friend’s perspective. What would they say about the flaw or situation you are struggling with? They might acknowledge that you feel bad about it, but also gently remind you of common humanity, that you are only human and no one is perfect. They would likely emphasise your good qualities and express unconditional care and forgiveness. If they suggested changes, they would do so with encouragement rather than criticism.

After writing the letter, set it aside for a little while. Then come back and read it to yourself slowly, letting the words sink in. You may even read it aloud in a warm tone. Allow yourself to feel the compassion in the letter soothe and comfort you. This exercise essentially gives form to your inner compassionate voice. Each time you feel self-critical about that issue, you can re-read or recall the letter’s message to reinforce a kinder perspective.

Working with the Inner Critic

You cannot simply banish the inner critic. It is a part of your Threat System trying to protect you, albeit in a maladaptive way. The goal is to alter your relationship with it.

When the critic starts speaking, pause and note it. “Ah, the critic is here.” Then ask, “What is this voice trying to protect me from?” This might be fear of rejection, fear of making a mistake, or fear of not being good enough. Next, respond with compassion. Do not fight the critic. Speak to it kindly but firmly. You might say, “I know you are worried and trying to keep me safe, but your harshness is hurting me. I’ve got this.” Finally, consciously substitute the critical thought with a compassionate coaching thought. Instead of “Don’t mess this up,” try “You’ve prepared for this. Just do your best.”

With repetition, your inner critic will gradually lose its dominance and a more compassionate inner voice will become your new normal. You will find that you can still hold yourself accountable and strive for improvement, but without the cruelty.

Loving-Kindness Meditation

Loving-kindness meditation is a traditional Buddhist practice that has been extensively studied in psychological research. In this practice, you deliberately generate feelings of kindness and goodwill, first toward others and ultimately toward yourself.

Begin by settling into a comfortable position and bringing to mind someone who naturally makes you smile. This might be a loved one, a child, or even a pet. Allow yourself to feel the warmth and care you have for this being, noticing how your body feels in this moment of connection. Then silently offer them phrases of goodwill, such as “May you be happy. May you be healthy. May you be safe. May you live with ease.”

After extending these wishes to someone you love, turn them toward yourself. “May I be happy. May I be healthy. May I be safe. May I live with ease.” This can feel awkward at first. If so, imagine what a dear friend who truly knows and loves you would wish for you, and offer yourself those wishes. The practice can gradually expand to include neutral people, difficult people, and eventually all beings everywhere.

Studies have found that people who engage in loving-kindness meditation regularly show increases in self-compassion, empathy, and positive emotions, along with decreases in self-criticism and negative rumination. Brain imaging research even suggests that such meditations strengthen areas associated with emotional regulation and empathy. Just as you can strengthen a muscle by exercise, you can strengthen feelings of compassion through intentional meditation.

Soften, Soothe, Allow

This practice is specifically designed for working with difficult emotions that have taken up residence in the body. When you notice you are struggling, locate where you feel the stress or discomfort physically. Perhaps it is tightness in your chest, heaviness in your shoulders, or a knot in your stomach.

Rather than trying to make the sensation go away, soften around it. Let the muscles relax, as if your body were melting around the discomfort. Then soothe yourself, perhaps by placing your hand on the affected area and offering kind words as you would to a beloved child who is hurting. Finally, allow the discomfort to be there. Let go of the urgent wish for it to disappear and let it come and go as it pleases, like a guest moving through your home. Repeating the words “soften, soothe, allow” can help guide you through this process.

Part Nine: Integrating Self-Compassion into Daily Life

Developing self-compassion is much like building any healthy habit. It takes consistent practice and patience. It can feel uncomfortable at first, especially if you are used to being very hard on yourself. But every time you practise one of these techniques, you are retraining your brain. The goal is to move self-compassion from a temporary “state” that you access during formal practice to a stable “trait” that characterises who you are.

Consider starting a self-compassion journal. Each evening, write down something that was difficult that day, perhaps a mistake you made or a challenge you faced, and then write a few sentences reflecting on it with the three aspects of self-compassion. For mindfulness, acknowledge “Today was hard. I felt angry at myself when I missed that deadline.” For common humanity, remind yourself “Everyone slips up sometimes. I am not alone in this.” For kindness, write “I tried my best today. I am going to cut myself some slack and get some rest. I care about my wellbeing and I will try again tomorrow.” Research shows that even brief daily self-compassion journaling can significantly reduce depression and increase happiness.

Beyond formal exercises, look for informal opportunities to be self-compassionate in everyday life. When something goes wrong, treat that as a cue to check in with yourself and apply kindness. It can be as small as taking a deep breath and saying, “This is tough. May I be kind to myself in this moment.” If you find yourself saying “I should be better” or “I’m so stupid,” use it as a prompt to pause and reframe the thought. Over time, these little moments of turning toward yourself with care add up. They build the inner resource of self-compassion so that it comes more naturally when bigger storms hit.

Consider using transition points in your day, such as leaving work, starting dinner, or going to bed, as moments to take a micro-pause and reset your nervous system with a breath and a hand on your heart. Use mindfulness to savour positive moments. This builds the resources of your Soothing System.

Ironically, self-compassion makes us better partners, parents, and friends. When we can soothe our own emotional needs, we are less dependent on others to validate us. We are less reactive in arguments because our Threat System is not constantly triggered. Research shows that self-compassionate people are more compromising in conflicts and more supportive of partners. In parenting, self-compassion is vital. Parents who practise self-compassion are less stressed and model emotional resilience for their children.

Conclusion: Becoming Your Own Ally

The journey toward self-compassion is not a straight line. It is a winding path of unlearning years, perhaps decades, of self-criticism and cultural conditioning. It involves the courageous act of turning toward your pain rather than running from it.

But the rewards are immeasurable. The science is clear: self-compassion reduces anxiety and depression, boosts the immune system, enhances motivation, and builds resilience against trauma. It allows you to access the best parts of your neurology, the parts designed for connection, safety, and care. It creates a more stable and positive relationship with yourself, one that is not contingent on success or dependent on comparison.

By adopting the practices outlined in this guide, you are not being selfish or indulgent. You are engaging in a rigorous, evidence-based process of emotional training. You are learning to be a good friend to yourself, someone who sticks by you when times are tough, offers a hand when you stumble, and reminds you that, no matter what, you are worthy of care.

Remember that perfection is not the goal. The goal is simply to be a little kinder to yourself today than you were yesterday. In a world that can be harsh and demanding, becoming a sanctuary for yourself is perhaps the most radical and necessary act of all.

Self-compassion is ultimately about embracing yourself as you are: a human being who is inherently worthy of care. It is about learning to treat yourself with the same empathy, patience, and gentleness that you extend to those you love. By doing so, you create an internal environment that supports healing, growth, and resilience. Life will always have challenges, but with self-compassion, you will face them with a wise and caring friend at your side. That friend is you.

Key Resources and Further Reading

Dr Kristin Neff is the pioneering researcher who operationalised self-compassion for scientific study. Her website (self-compassion.org) offers free exercises, guided meditations, and links to her books including Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself.

Dr Christopher Germer co-developed the Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) programme with Kristin Neff. His book The Mindful Path to Self-Compassion is an excellent practical guide.

Professor Paul Gilbert is the founder of Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT) and developed the “Three Circles” model of emotional regulation. His books include The Compassionate Mind and Compassion Focused Therapy.

Dr James Kirby is Co-Director of the Compassionate Mind Research Group at the University of Queensland and a leading Australian voice in compassion research.

Centre for Clinical Interventions (CCI) based in Western Australia offers free, high-quality workbooks on self-compassion and other mental health topics at cci.health.wa.gov.au.

This Way Up (St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney) provides evidence-based digital mental health courses including modules on self-compassion at thiswayup.org.au.

If you have a history of severe trauma or find that self-compassion practices bring up overwhelming emotions, working with a trauma-informed therapist trained in Compassion Focused Therapy is recommended.